Student evaluation is a slippery thing.

First, you have kids, who are growing each day on cellular as well as cognitive levels. Moving targets, if you will, for assessment. What may have been true about a kid on October 1st is quite possibly no longer the case on October 15th.

And then you have institutions with their recordkeeping mandates. Tools are in place to enable teachers to check off rubrics, enter generalized remarks, and also, where possible, add a blurb of personal commentary about a student. And tests—with publicized results— yield further measurement data to demonstrate to state departments of education and to the federal government whether or not Billy and Susie are being left behind.

And then you have a person like me—the parent—who is unsure about the rationale for, and the manner of, assessments of my children by others. By relative strangers.

Thousands of years after great cities and civilizations sprang up, hundreds of years after the Enlightenment in Europe began freeing Western minds, and now in the second century of American public education—which purports to be the great meritocratic equalizer—I just have to wonder: What is better in the schools of today than one hundred, two hundred, even five hundred years ago? Does our system work all that well? And does our system of student assessment inspire kids? Or parents? Does it get the teachers anywhere? What, in fact, do grades ultimately accomplish?

I have only my own lifespan of personal experience to go on as direct evidence, so I must contend that I am no more convinced today than I was 40 years ago of the benefit of giving children grades in the way that schools do.

The elementary school I attended in the 70s practiced qualitative assessment. Every six weeks, my parents received a stack of handwritten half-sheets with each of my teachers’ narrative comments about how I was faring.

Once 5th grade rolled around, these narrative comments continued, but grades were attached: not A-F, but rather a grading scale based on 5. For example, a “5+” was the same as an A+, “4” was a B, and “3-” was a C minus. Getting a 2 was getting a D, and there was a “1”—a rarity at my school—to represent an F.

It kind of made outside praises like You’re Number 1, kiddo! sound confusingly like an insult.

But even dumber was that the staff at this little private school all seemed to think that we wouldn’t be as grade conscious using these numbers rather than letter grades.

Riiiight. Did they really think we could be duped so easily?

We’ll use a 5 instead of the letter A, and so on. Who, I ask, thought that one up? I hope whoever he is, he’s enjoying his Price Is Right show this morning in that Florida condo…the dumbass.

Oh, educators. You graded us…you never let us grade ourselves. Those five numbers and the plusses and minuses you threw in loomed large, larger than the material you were supposed to teach. And whether we kids acted like we cared about grades or not, we all took a hit deep down inside. You taught us not only fear of failure, but also how to be insincere in our learning—how to shamelessly become teacher-pleasers prioritizing your evaluations rather than even thinking about our learning processes. Once we were divorced from any and all concern about the why of our developing aptitudes and skills, it was easy not to care about the why or how of our education year after year.

Flash forward to Europe, where I went to college. I recall European classmates telling me about their 11’s. Eleven, apparently, was a terrific grade.

But wait—there was 13, too.

“Thirteen?” I asked one guy. “But what about 12?”

“Oh,” he beamed, “there is no 12. It doesn’t exist. Because to get a 13, which is so rare, you have to be that much better than anyone in the realm of 11.”

A grade of 13, then, was reserved for Stephen Hawking types. For those off-the-Richter talents whose mere presence in class made a mockery not only of the rest of the group, but the teacher as well. From what my friend described, a 13 meant that the kid would get a place in university, bee-lined for eggheaded greatness. There’d probably wind up being a bust of him or her somewhere, someday, in their little cobblestoned hometown.

I wondered, of course, what our American A+, A, and A- would translate to in that European system. How many minuses or plusses would need affixing in order for an A to convert with any accuracy? Would a regular A be…just a 10? An A- a 9? Would the higher levels of A-ness be kind of like one Hollywood A-lister being hotter than another, like George Clooney? How much greater than great is “greater than great?”

It makes a person wonder: Aren’t great and superlative quite often subjective notions?

My kids have had the modern 4, 3, 2, 1 system in the public schools. There are no A’s and there are no plusses or minuses, at least not on their progress reports. I’ve heard that it’s a device to get families and kids away from the “getting an A” mindset. A grade of 3, for example, means that the child is “on track,” which in any decade of a parent’s or grandparent’s educational history could mean anything from a C to a B to an A grade. We’re stuck as public school customers with this 3-thing staring back up at us from the progress report, taunting us with Your kid is fine. Well, what kind of fine is he? Or…have you been too busy with standardized test prep to notice? Most parents I know read their kid’s progress report and come away none the wiser about their kid’s school experience than before.

In the 4-3-2-1 setup, there aren’t even five numbers for us to mentally map onto the A, B, C, D, E framework we’re familiar with; all there seems to be are these things known as “end-of-year expectations.” A “4” is not an A, nor is it a 100%. It’s only given in terms of exceeding grade level expectations. So if my kid does get a 4, it means that he has achieved or gone beyond the end-of-year expectations in that subject area for that grade.

Wow. Seeing that, I’d have to ask the teacher: Are you going to give him advanced work from now on, then, for that subject? Work equal to what is covered one grade higher? Because if he can already do everything you expect him to learn in here this year, won’t he be bored just marking time?

It turns the getting of 4s into…kind of a red flag. Uh-oh. He’s getting 4s.

My graded-4-in-reading boy was bored. Bored shitless. But in a room teeming with kids, in a district choked with professional development half-days off and pressure to study for standardized tests, there was no real differentiated instruction. He could have stayed quiet while bored, à la Patience, Grasshopper, but he made the mistake of showing it. Naughty boy, just being human. Next marking period, wouldn’t you know it, I saw 3s where the 4s had been. And in the comment box were remarks about his being a distraction to himself and others, and “not getting enough done in a day.”

I asked him about his grades and those teacher comments. He said he didn’t want to participate in the teacher’s classroom reading program, in which kids selected and read a certain number of titles each month, because he had shelves and shelves of books he liked at home, and what’s more, he didn’t really want the Pizza Hut certificate she gave kids as a reward. He said he didn’t like their pizza. “I’d have joined if there’d been Sushi Land certificates,” he added.

So my kid, who doesn’t care for Pizza Hut but who reads like a fiend in his free time, is now…a 3. Whatever that means. Have his cognitive abilities atrophied that much?

Wow. Maybe they have in her class. I’d better get the boy down to Powell’s Bookstore right away, for an infusion of Harry Potter and Spiderwick.

3, not 4.

Thanks, school. Your single-digit opinion is so eloquent. My son feels he got into some kind of trouble for reading too high, and now he feels he’s been given some sort of comeuppance. Overseas, that’s known as tall poppy syndrome.

3, not 4.

Like the Jack Russell terrier down the block who had to have a hind leg amputated.

3.

Like diarrhea.

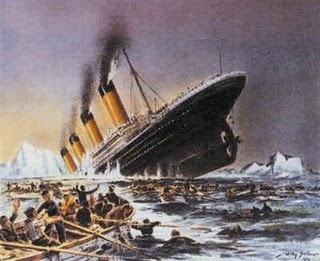

But school, I gotta say this: You never recorded one single instance of what he felt about the stories he read. How his sense of wonder or joy was sparked by a book or a comic. You never saw him drawing cartoons after reading Captain Underpants, or heard his voice rise while reading The Titanic aloud to his little brother as John Jacob Astor put his wife on board the lifeboat, then stayed behind on the sinking ship.

No. In one of your classrooms, nineteen of your 24 kids are turning in sheets listing all the titles they’ve read for the month, and so to you, that must mean that the other 5 kids are not reading. Not keeping up. Not being good, disciplined learners. Because reading only matters when it’s a competition. When a kid reads because he is being told to by a teacher.

Well, one of those five kids has a parent who says this: To hell with your 3s. We don’t even want your 4s. And we don’t want your certificates to feel rewarded and entitled to go out to eat. Food as a reward for reading? No. Food is only a reward in our house when the three of us have stood there and learned to cook it ourselves.

And learning how to read isn’t a race. We’ll get there when we get there. No teacher can ever make a kid like reading more. But she sure can make a kid like school a lot less with her arbitrary doling out of happy-numbers and angry-numbers.

4, 3, A+, B…see ya! We’re more interested right now in whether Mrs. Astor and those other women and children from the Titanic got rescued.

We’ve got something we’re reading together about a sinking ship.

A sinking ship…kind of like what your school looks and feels like, even though I’ve voted yes for all the levies to keep it afloat.

A harrowing tale of classroom-meets-iceberg. But we’ll survive.

We’ll just hope to have gotten 3s in oarsmanship as we row ourselves away from you.

Assessment, Elementary, General, International